【Risa Sakamoto Archives】

On Najwan Darwish

The Review’s Review

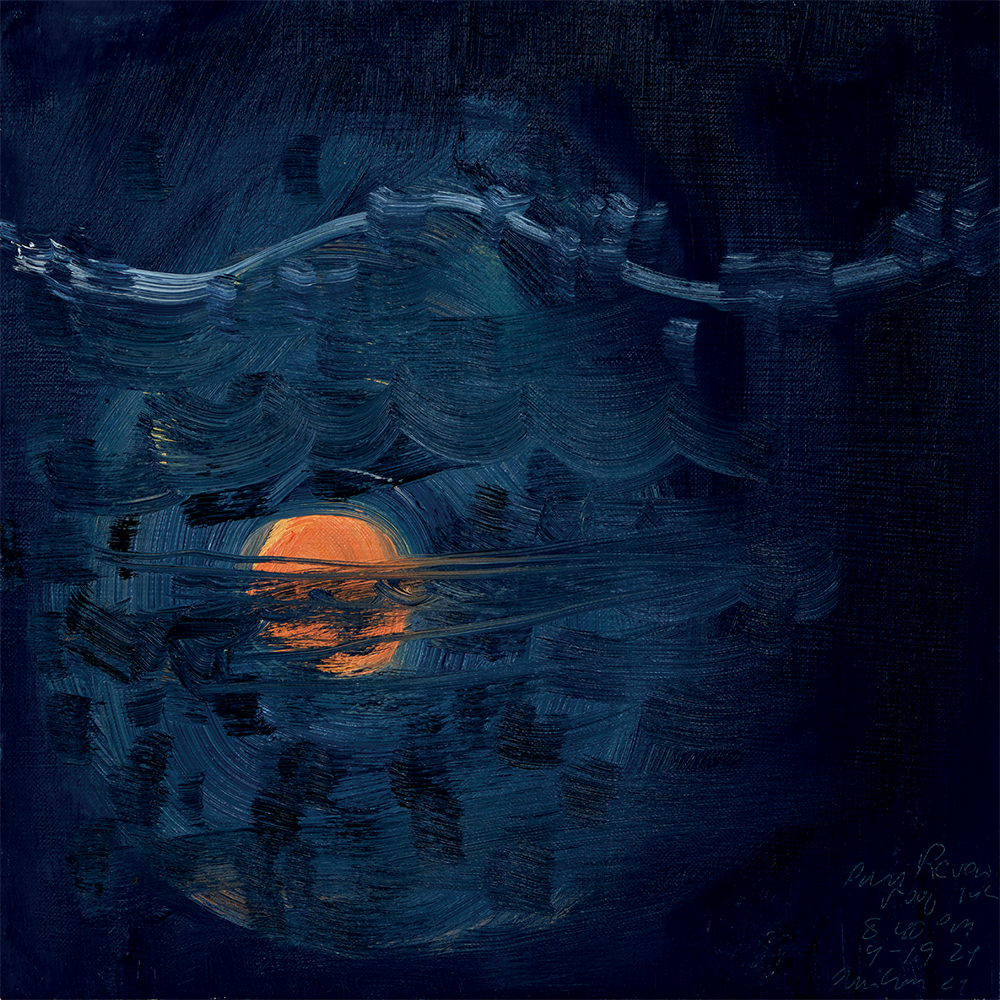

Ann Craven, Moon (Paris Review Roof, NYC, 9-19-24, 8:40 PM), 2024, 2024, oil on linen, 14 x 14″.

“No one will know you tomorrow. / The shelling ended / only to start again within you,” writes the poet Najwan Darwish in his new collection. Darwish, who was born in Jerusalem in 1978, is one of the most striking poets working in Arabic today. The intimate, carefully wrought poems in his new book, , No One Will Know You Tomorrow, translated into English by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, were written over the past decade. They depict life under Israeli occupation—periods of claustrophobic sameness, wartime isolation, waiting. “How do we spend our lives in the colony? / Cement blocks and thirsty crows / are the only things I see,” he writes. His verses distill loss into a few terse lines. In a poem titled “A Brief Commentary on ‘Literary Success,’ ” he writes, “These ashes that were once my body, / that were once my country— / are they supposed to find joy / in all of this?” Many poems recall love letters: to Mount Carmel, to the city of Haifa. To a lover who, abandoned, “shares my destiny.” He speaks of “joy’s solitary confinement” because “exile has taken / everyone I love.” Irony and humor are present (“I’ll be late to Hell. / I know Charon will ask for a permit / to board his boat. / Even there / I’ll need a Schengen visa”), but it is Darwish’s ability to convey both tremulous wonder and tragedy that make this collection so distinct.

Darwish has talked about the concept of poet as historian in interviews (“we drag histories behind us,” he has written) and No One Will Know You Tomorrowcontends with the grief of the Palestinian people since the Nakba of 1948 and amid the genocide currently taking place. But it would be a mistake to reduce Darwish to a “wartime” poet. As Abu-Zeid points out in his introduction to the book, Darwish is doing something more complex: writing across time and place, geography and religion; drawing on a deep well of artistic heritage to inform the present. (“My country is an Andalus of poems and water, / I lost it, / I’m stilllosing it— / in loss / it becomes my country.”) Darwish also brings the history of Palestinians in relation to those of other peoples in diaspora. For Armenians, Kurds, Baha’i, Syrians, and others, “the earth—all of it—is a house of refuge. / The people—all of them—are citizens of dust.” Literary figures, living and dead, haunt these pages, from legendary pre-Islamic poets like Antarah and Sufi mystics to the Egyptian poet Hafez Ibrahim and the Syrian poet Adonis. “I have so many friends / sleeping in tombs from different ages— / at night I tell them stories, / more often than I should,” he writes in a poem dedicated to Yahya Hassan, the Danish Palestinian poet who died in 2020. “Come tell me stories and stay / above the ground. I’ve company enough already / beneath it.”

Darwish rarely gives interviews, but I spoke with him for theGuardianat the end of 2023. He was grappling with the horror of Israel’s war on Gaza, which has left more than forty-six thousand Palestinians dead and injured and displaced many more. It has taken his friends and fellow artists; wiped out entire families so there’s no one to call to express condolences, he said. Images of Gazan children haunt him. He spoke to me about filling a notebook with poems after October 7 and losing it at an airport; he thought he might never write again. Notebooks appear in several poems in No One Will Know You Tomorrow (“the last page in a notebook, / the last lip, / the last finger, / the last thread of light, / the last bit of darkness”), and I came to see them as a sort of talisman against forgetting: a way to record the dignity of Palestinians, and a bulwark against the colonizers that rewrite history to their advantage.

The last poem in the collection, “Endless,” could be read as an elegy, or a ringing call to action—even if that action is to, against all odds, survive. “In utter darkness, / in light, / in ruin, / in psalms, / in a trumpet, / in the horn of Israfil, / in a labyrinth,” he writes, “in an end that leads / to an endless end, / I lived.”

Alexia Underwood is a writer and award-winning journalist who was born in Kuwait and grew up in Egypt and the U.S. She’s currently at work on a novel.

Search

Categories

Latest Posts

Best iPhone deal: Save $147 on the iPhone 15 Pro Max

2025-06-26 15:49Precious National Park Service denies permit for 45

2025-06-26 15:11'Stranger Things 2' solves the mystery behind Steve's hair

2025-06-26 15:03CPU Price Watch: 9900K Incoming, Ryzen Cuts

2025-06-26 14:29Popular Posts

Teforia, startup that made $1,000 tea infusers, calls it quits

2025-06-26 15:52Popular sports video game allows for characters to come out as gay

2025-06-26 15:43Read Zachary Quinto's note in response to Kevin Spacey's coming out

2025-06-26 15:33U.N. confirms the ocean is screwed

2025-06-26 14:39Featured Posts

Against Fear

2025-06-26 16:51Trump's transgender military ban blocked by judge

2025-06-26 15:46Popular Articles

Why Building a Gaming PC Right Now is a Bad Idea, Part 3: Bad Timing

2025-06-26 16:33Millie Bobby Brown still stuns as Eleven in 'Stranger Things 2'

2025-06-26 15:41Facebook's opaque algorithms, not Russian ads, are the real problem

2025-06-26 15:35Holy waffles, we have the best 'Stranger Things' costume right here

2025-06-26 14:42Best Sony headphones deal: Over $100 off Sony XM5 headphones

2025-06-26 14:29Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest updates.

Comments (4661)

Music Information Network

NYT Connections Sports Edition hints and answers for April 23: Tips to solve Connections #212

2025-06-26 16:52Ignition Information Network

Clear pumpkin pie is a thing

2025-06-26 15:58Unique Information Network

How to make hard decisions by removing yourself from the situation

2025-06-26 15:37Exquisite Information Network

Millie Bobby Brown still stuns as Eleven in 'Stranger Things 2'

2025-06-26 14:56Openness Information Network

Character AI reveals AvatarFX, a new AI video generator

2025-06-26 14:44